Top O' the Mountain

Friday, April 12, 2024

2024 Solar Eclipse—Junction Texas

Monday, January 1, 2024

Books 2023

NON-FICTION

He goes into a strongman's nationalistic tendencies (and nationalism is not the same as patriotism), the disregard for long-standing institutions that have served the people well. It's disconcerting to know that if this keeps up, freedom and democracy will fall by the wayside. Why some think that is a positive thing is beyond me. Some proclaim that "democracy doesn't work," but it does work--it's not perfect--but it has led to the most prosperous and healthy societies in history. What other form of government works better? Certainly not Saudi Arabia's where portions of the population are denied rights, certainly not Russia's where one can be arrested for voicing an opinion.

By the way, the author is a journalist who personally knows some of these strongmen.

Butler to the World***1/2 by Oliver Bullough: Picture the role of the English butler in many a PBS production, and then think of Britain in that role of serving, supporting and enabling those lyin' cheatin' folks who use Britain's loose policies and laws to advance their own financial welfare. Corruption on a huge scale happens right under the nose of the government, and few seem to care.

The Choice***** by Edith Eva Eger: Wow, everyone, and I mean EVERYONE, must read or listen to this book. The theories Eger espouses are not new or revolutionary, but to hear them explained by someone who has every reason to wallow in anger, misery, and fruitless wishing that things were different, is extremely effective. Through her practice as a psychiatrist, Eger not only helps others but helps herself to understand her own tragic experience at Auschwitz, and to forgive herself for sending her mother to the gas chamber. Of course, this was not a deliberate action, but because she told a Nazi the woman with her was her mother, rather than her sister, her mother was deemed too old to work and was killed.

I saw myself several times in the book. The first was the trauma I suffered as a barely 4-year-old when my Mom was losing a baby. There was blood everywhere, and Mom asked me to run next door for help, which I did. For a long time that nasty woman next door would laugh at me for coming to her door that day and just standing there, scared and speechless. It made me feel like I had done something terribly wrong. Though Mom defended me and insisted I did everything right (and she surely had words w/ that neighbor), it wasn't until in my 40s when I made a 'pilgrimage' alone to my brother's grave, that I could lay this trauma to rest.

At one point in the book Eger talks about her daughter unconsciously trying to make up for the childhood her mother had missed out on. I grew up knowing that a certain branch of my Mom's family had basically saved her dirt poor struggling branch. In the 90s a distant cousin from this good family moved near me, and I found myself constantly thinking of ways I could serve and help her. We had them over regularly, I babysat her little boy, hired her to teach my kids piano, etc. Anything I could do to show how much her family was appreciated by Mom and hers.

So, this book helped me to look inside myself to identify ways in the past I had felt inadequate, and also made me realize that though I understand forgiveness, I have not forgiven everyone and must. Eger ends with a profound personal experience and proclaims that we are FREE to choose to live in the presence and look to the future.

The Escape Artist**** by Jonathan Freedland: In 1944, a Jewish teenager named Rudolf Vrba became the first Jew to ever break out of Auchwitz. His purpose was to reach authorities who would hear from him the reality of what was going on in what came to be called a death camp, or an extermination camp. The intricate plan that would take him and his friend Fred out of the camp safely was actually rather crazy. They studied the patterns of life in the camp, the patterns of the Germans, the patterns of other prisoners, and then camp up with a way to get out, and they did. However, he was later extremely sad and frustrated that authorities either didn't take him seriously, sat on the report, or felt it was someone else's job to look into it. All the while Jews were dying by the thousands every day.

Eventually his voice was heard, and in the end he probably saved several hundred thousand Jews. An intriguing story!

The author chronicles actions and attitudes of a number of prominent party members and also elected Republicans who spread conspiracies with zero regard to actual facts. I'm writing this on March 10th, just days after Carlson of Fox edited January 6th video footage to "prove" that the invaders of the Capitol on January 6th were just happy tourists taking selfies. So there you go.

To demonstrate the weirdness of the conspiracy-espousers, Marjorie T-G and others of her ilk are extensively quoted on topics of the insurrection, Covid, pedophilia and other topics. Whether those spouting the craziness really believe their words is less important than the damage they do by peddling their thoughts to less-informed folks who eat it up.

The book is biased and sometimes snarky yet well thought and written.

The Petroleum Papers***1/2 by Geoff Dembicki: I almost didn't listen to this one as the subject doesn't grab me. It covers climate change, and the role of big oil and other industries in sweeping it under the carpet for decades. Now we're facing a crisis that could have been addressed, and solutions could have already been in place.

Like a lot of people I sort of tune out talk about climate change. I admit to not having studied the facts, so I rely on my own minimal knowledge here. Hasn't Earth always had major storms, fires, and other such damaging events? The answer is yes, so what is different now? Because we have instant access to any type of information, and news outlets are competing for prominence, are not all of these events over-hyped? The answer is yes. In the past we had rain, or maybe 'pouring rain.' Now we have bomb-cyclones and mega-droughts and atmospheric rivers, and so on. The difference between then and now is that a lot more humans are living in areas where the above occurrences more strongly affect populations than in the past. So, ok.

The author presents evidence that those who have and do prosper from industries that create environmental problems, went to great lengths in the past to cover up their knowledge, and to continue doing what they did no matter the cost to our environment and to our climate. His biases show through, just so you know.

Under a Flaming Sky**** by Daniel James Brown, second reading: Events of a day in Hinckley Minnesota in 1893 when a firestorm engulfed the town. This story is so gruesome, yet told in a very humanizing way.

The Swedish Art of Aging Exuberantly***1/2 by Margareta Magnusson: Full of charming and well-tested advice about ways to enrich your life and the lives ot those around you. It goes along with a book called The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning. The latter discusses how to get rid of things so that your family won't have to do it after your demise (I have not read this one yet). I like her aging philosophy. Not much of it was new, as I had sensible parents, yet it was fun to read.

The Ruin of All Witches**** by Malcolm Gaskill: 17th century Springfield Massachusetts was a typical settlement of the time. A small group of immigrants from England made a new start here along what came to be named the Connecticut River. Life was harsh, life was scary, life was devastating. Early death, disease, crop failure, stern religious protocol all served to create despair, depression, fear and suspicion. A fascinating, tragic chronicle, it is easy to be washed with horror and pity for those stuck in that place at that time. I highly recommend, if for no other reason than that a reader will come to rejoice in their own lives and circumstances.

The Magnificent Lives of Marjorie Post***1/2 by Allison Pataki: I loved this book. Post was a woman who made things happen, taking after her father in many ways. He began the cereal company that became General Foods, and even today the Post is still on some of the products. She was mightily wealthy and her personal life was a wreck, but that didn't stop her from enjoying life and doing good along the way, and telling us all about it.

However, I give it a slightly lower rating than it deserves because it was written as a novel, but had non-fiction elements. At times I was confused. I wondered from time to time what was real and what was not. Many conversations were created and it seems weird that on picking it up you think it's going to be a biography, but then it can't be that. Still riveting though.

The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window*** by Jonas Jonasson: This book is a sort of a Forest Gump-style story. An old man escapes his 100th birthday party in a nursing home by climbing out the window, and then his amazing adventures begin. He seems to always end up in the right place at the right time to solve some world problem, or make friends w/ gangsters or whatever. It was good, but not great. Fun to read though.

Seventy Times Seven**** by Alex Mar: A story of evil and forgiveness. An elderly white woman is murdered by several black teen girls. One is sentenced to death at age 15. Eventually a son of the victim forgives and befriends the girl. She begins to believe in herself and desires to make something of herself. The victim's son is maligned by others, even by those in his own family. The book examines what it means to forgive, and how that affects the perp in this case, and everyone else involved. It makes one think about the definition and meaning of justice. It's a moving story.

Planet Funny*** by Ken Jennings: Sort of a history of humor-comedy. It's a good book. The reason for only three stars is personal, and it ages me. Much of the humor he referred to is from shows or programs or people I am unfamiliar with, so I didn't 'get' it. My kids might relate to this better. But still, I'm glad I read a book that explains the evolution of humor.

The Ship Beneath the Ice***1/2 by Mensun Bound: More than 100 years after the crushing and sinking of the ship Endurance in 1917, captained by the famous explorer, Ernest Shackleton, a crew intends on locating the ship beneath the ice. Bound is a Marine archaeologist, and the Endurance is trapped beneath the Antarctic Ocean, the most hostile area on earth. It's a thrill to follow their progress and to comprehend the shocking obstacles barring them from finding the wreck. At times it dragged on, but in the end, a good story. Bonus, the author mentions the polar explorer Tom Crean, who was from a village a few miles from my ancestral villages. My ancestors would have known Tom Crean as a child.

A Fever in the Heartland**** by Timothy Egan: I had no idea. Author traces the rise of the KuKluxKlan in America post World War One. The Klan to me had been a way for racist white men to terrorize Black people post-Civil War. And they did. But later on the Klan rose to prominence in most areas of the US, including where I live in Oregon. The author focuses on Indiana, and recognizes the problem was widespread. The Klan stacked the police force with members, the local governments, and even higher levels of government. He uses David Sutherland as an example of the depravity of the Klan. Though they espoused ideals such as the sanctity of marriage and respect due to women, it wasn't uncommon for the leaders to secretly use their power in antithesis to the supposed ideals. One woman who was badly mistreated by the above eventually brought him down, though she lost everything by doing so. What a revealing book about a part of America's history not often talked about.

Agatha Christie*** by Lucy Worsley: I like Agatha Christie's works, although am not a major fan. The book was quite interesting though. The author examines deeply the facts of Christie's life. Her failed marriage, second marriage to a very much younger man, her archaeology adventures, her finances, and the way she wove themes from her own life into her novels. The author feels the latter helps understand times in Christie's life that are obscure and unmentioned by Agatha herself, yet the fiction can be extrapolated to revealing more about her life. Like many well-off people in the past, there are contradictions. When Christie was still young, her father died, and so rather than staging Christie's entrance into society within London circles, her mother took her to Cairo where it would be less costly. Wow, how poor can you be to take a trip to Cairo just for that!!

Slouching Towards Utopia**** by J. Bradford Delong: Author covers period of late 19th century to the first years of the 21st, examining progress in a number of categories, and focusing on why all of the advances have not brought earth-life into a utopia of existence.

Spare**** by Harry Wales: Y'all know Harry Prince of Wales and his wife Megan (she of the pocketed dress)!. I was a little annoyed at how much Harry doesn't seem to appreciate his ease of life. As a child he never had chores, and through his life has had plenty of funds to ride horses, vacation, or whatever. But if all he says is true, his life isn't so rosy. The expectations of the Royal Family are demanding, even impossible, and at the same time it seems he hasn't been well-treated. Maybe that's the understatement of the year. From his point of view a break with the royals was a necessity, not a choice. It's hard for Americans to comprehend royalty in the first place--you have all this money and position that you have not earned, it was just thrust upon you at birth. Then, Harry being the second child of the future king (the "spare"), he didn't seem valued and seemed a disappointment to the family. He now has taken control of his life and is living the choice he made. Well worth reading.

The Wager**** by David Grann: What a real life thriller! You know how we read something about the past and think "I'm glad I live now!" Well, after reading The Wager I'm really really glad I wasn't an 18th century seaman. What a harsh, horrible life. Well, you can tell the book enlightens us on the life of a sailor of the past. In this case, the ship Wager was wrecked off the coast of what is now Chile, circa 1840. And then the battle for survival began. That included mutiny by some. Others were left stranded on an island, some were washed into the sea. To use a common phrase here: this is a real page-turner!

The Lost City of Z***1/2 by David Grann: The author traces the journey of British explorer Percy Fawcett, who disappeared in the Amazon while on a quest to find El Dorado circa 1925. Not my favorite Grann story, but a riveting adventure!

Goodby Eastern Europe**** by Jacob Mikanowski: The book I've been waiting for, for half my life. Author gives a history of what we call Eastern Europe, an area which is often passed by in publications. [often what I do find written about the area is in a Slavic language]. He moves forward in time discussing periods, kingdoms, religions and culture. Love it.

I Am Malala***** by Malala Yousafzai & Christina Lamb: Everyone knows who Malala is and why she is a public figure worldwide. I knew none of her background and found this book fascinating and inspiring. At first though, I thought she might be sugar-coating her father's determination to stand up for the rights of girls and women, especially in the field of education. But I did other research and found his position is as she said. I love knowing that everyone can do something to make the world a better place. My efforts are small, hers are large, and that's ok.

What a shame that she has been maligned on that doggone social media, where people with nothing else to do can anonymously condemn someone else, can twist the facts, or just make up "facts." Some accused her of arranging the shooting to get publicity for her cause. Yeah, a 15-year-old arranges for someone to fire 2 bullets into her head. Another ridiculous one is that she was-is a CIA agent. Again, a teenage girl? Or that her father is the agent of the evil decadent West . . . etc. etc. She had the guts to go up against the Taliban, those manly brave soldiers who get their jollies from keeping down half the population. And yet they had to prove themselves by shooting a threatening child. . .

The Art Thief***1/2 by Michael Finkel: Stephane Breitwieser is one of history's most prolific and famous art thieves. He perfected his methods over several years and became bolder, took serious risks, and then finally paid a small price. He was brash enough to stick paintings underneath his jacket or small items in his pocket or in his girl-friend's purse. It is astounding to think that he excused his thefts by saying he could preserve the art and would return it someday. He stashed it in his attic causing some pieces to be permanently damaged. Then horror of horrors, when he was caught some of the art "met its maker." The book is interesting though not riveting.

Fatherland**** by Burkhard Bilger: This is an intriguing book that will interest readers who would like a very personal account of the trials of the two World Wars in Europe. The author's ancestors were from Alsace, and if you remember high school history, this border area between France and Germany slid back and forth between the two countries. The author's grandfather was a school teacher, and a member of the Nazi party. I am astounded at the author's success in locating rare resources that fleshed out the life and personality of this grandfather. Given that the area saw action during the two wars it seems there would not be much of a record left of anyone. He also describes the horrors endured by family at home. Excellent.

The Golden Thread***** by Kassia St. Clair: What a deliciously, almost tactile examination of the evolving of textiles in world history. I loved every bit of her stories of how various fabrics came into being, how they were used, and their value to societies. Cotton, wool, silk, denim, rayon and so on, she explains how they were harvested and then woven into usable items. She discusses the environmental and societal impact of each. Lovely book! One of my favorites!

Enough**** by Cassidy Hutchinson: Another of a pile of books written by former Trump staffers, former Trump lawyers, and journalists. Hutchinson is best known for the famous photo of her swearing in in front of the January 6th Committee in 2022. She was all-in in the Trump administration and at a very young age landed the job as the chief assistant to Trump's chief-of-staff, Mark Meadows. She was regularly in the presence of the President, and rubbed shoulders with many who served in his administration.

When she came to the attention of the January 6th Committee, she agonized about testifying. She realized what she had seen and heard was not what an American President and his staff should be doing and saying. Yet she was torn about making public information that would be damaging to the President and his closest advisors; her loyalty was to her employer, but in the end, she realized her loyalty belonged to country. She testified several times between closed doors, and eventually testified in public.

The book itself was dull in the beginning because she went into detail about her early life. That seemed presumptuous given that at the writing of the book she was only in her mid-20s, so there wasn't much to write about. Also, the people she talked about are still living, and I'm sure they aren't thrilled with the way they come through in the book. After that the book picked up speed and I found it fascinating, a first-person insider's look at what really went on in the White House in the last part of the Trump administration. Her experience testifying and the difficult aftermath gave me a lump in my throat. Her life post-testimony is not easy.

A Thread of Violence**** by Mark O'Connell: Book profiles the life of an Irish murderer--Malcolm McCarthy--who in the 80s took 2 lives, savagely. The story is based on many interviews between the author and the perp, who was released from prison after a time. It isn't so much about the crime as about the psyche of the perp, and it's fascinating. McCarthy is from a gentile well-off family, and sees himself as part of that class, even after the murder. The act of murder does not define him, he says; it's just something that happened to him, but it's not who he is. The author reminds him multiple times that he IS a murderer. He has disassociated himself from the crime and sometimes refers to it in vague terms, such as "2 people were killed," or "they lost their lives." In his mind he has pretty much removed himself from the crime. It was shocking to me to hear his reference to the first crime, where he beat a woman so badly that she later died, and he states that when he walked away from her, she wasn't exhibiting any distress. What the heck! Yeah, because she was almost dead and unable to express herself. So strange that he can rationalize and justify his actions.

The Heat Will Kill You First***1/2 by Jeff Goodell: Author reviews the modern occurrence of heat extremes devastating the earth, and how far-reaching the effects can and will be. Forest fires, melting ice, and longer summers will devastate our food supply and even directly kill significant numbers of people. I think what ordinarily keep me from reading a book like this is that I get sick of hearing every time it rains hard or is hot for more than a couple of days, and so on, that 'climate change' is responsible. I assume it has always rained hard, and at times has been hot for days, so what's the big deal? It can be presumed that the climate has always been changing and evolving, but until the last small slice of earth's history, there haven't been many people around to be affected by it. Now is different. Anyway, the author reasons out the problems we are facing due to greater heat, and incidentally, he starts out by describing the unprecedented heat wave that hit the Pac NW at the end of June 2022. I lived through it and it was dreadful. 115-116 degrees for three days, at least 10 degrees hotter than ever previously recorded here. So that got my attention.

Bad Bridget***1/2: I tend to think that Irish immigrant women were all like my ancestors: faithful, giving, funny straight-arrows. But no, this book goes into the life of crime lived by some Irish immigrant women. It covers everything from kidnapping, theft, prostitution, and so on. I love that the title of this is Bad Bridget. The name Bridget was used generically as a term for Irish immigrant women, particularly housekeepers. Even my own father objected to me naming a child Bridget, because he was aware of that connotation!

Foreign Bodies ***1/2 by Simon Schama: A chronology of the development of vaccines. He covers smallpox, plague, cholera, etc. In my humble opinion, the development of vaccines is one of the world's greatest blessings and accomplishments. As a researcher, I've seen heartbreaking situations in death records and in old newspapers, where large numbers of people die from afflictions we hardly give a thought to now. The author points out that not all vaccines were developed first in the lab by white-coated scientists. Smallpox was first prevented by women in country villages who understood how to inoculate against the disease.

Democracy Awakening*** by Heather Cox Richardson: An analysis of how and why we must re-commit to Democracy. Interesting and worth reading. Heather is much more liberal than I am, and I like reading thoughts that are expressed as well as hers.

;

The Arab Winter**** by Noah Feldman: We all remember the hope that spread across the world when the Arab Spring began in Tunisia in 2010. Author reviews country-by-country what has happened since, and little of it is good. Egypt for example, got rid of their dictator, Mubarek, and then found his replacement intolerable, and now they're back to a Mubarek-like leader. We all know what has happened in Syria: a dictator whose only goal is to stay in power, and as a result, has allowed his country to be destroyed. On a personal note, when I visited Hama, Syria in 2005, I learned what the elder Assad had done there in the 80s, and figured that his western-educated more progressive son would never be that bad. But I was wrong; he's light-years worse.

This is an excellent book for helping one understand the difficult situation in the countries of the ME. I highly recommend.

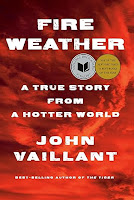

Fire Weather****: Fort McMurray Alberta, a place I never heard of until now, is the hub of the Canadian oil industry. In 2016 it was hit by wildfire that destroyed neighborhoods, forests, and businesses. The author's premise is to tell us to get used to this type of event. He supports this by going into climate science, which I found mostly interesting. He also describes how this fire happened, and some strange and extreme phenomena associated with it Very fascinating. Tens of thousands of people were evacuated. At one point, to prevent a firestorm, crews bulldozed houses ahead of the fire by pushing them down and into their basements. Then they towed cars on the street onto the piles in the basements. I couldn't put this book down.

FICTION